The Palaeontological Association was founded in 1957 following a number of meetings and discussions among young palaeontologists in the southeast of England, the first of which took place in a London taxi. Sixty years later, although most of our Council meetings still take place in London, the Association and its Annual Meeting have become genuinely international in both outlook and representation. On the following pages are a few recollections and reminiscences from some of the Association’s founding and honorary life members, including some present at the inaugural meeting and involved with its organisation, some recalling the inception of the PalAss, and others comparing how the publications and public meetings have changed over the last six decades. Our publications continue to grow while retaining their high standard and contribute greatly to the income that keeps the organisation buoyant. This growth in income and investments now allows the Association to reinvest in research, public engagement and the support of early career palaeontologists at a level of around £80,000 per year.

One of the biggest changes over the past 60 years is the global reach of the Association, as it has expanded almost exponentially from a small London and UK-based learned society to an organisation with a global membership of well over 1,000. Currently there are members in 48 countries, from Austria to Zambia, many of whom travel to the Annual Meeting each December to present their research and take part in lively discussions. We hope that you will be joining other PalAss members for the Annual Meeting in December 2017 at Imperial College London, back where the inaugural meeting was held in 1957.

Professor Paul Smith

Director, Oxford University Museum of Natural History

President, Palaeontological Association

Palaeontological Association History

… or “The origin and early evolution of the Palaeontological Association"

(or, “Who was really in the taxi?”)

Note: This account was written as an after-dinner speech by Professor Frank Hodson (1921–2002) of the University of Southampton and was delivered on the occasion of the 25th Anniversary Dinner at the University of Sheffield during the 1982 Annual Meeting. The text was first published by the University of Southampton in 1983, and was reproduced in the Palaeontology Newsletter (no. 64) and here with kind permission. According to his obituary in Newsletter 52, Frank Hodson was an accomplished orator and one of his favourite themes was the founding of the Palaeontological Association, of which he liked to say “it was born in a taxi”. However, the legendary taxi ride in which the idea of the Association was first conceived has been subject to embellishment over the years, with many different people thought to have been in the taxi; in the text below Hodson sets this matter straight. The Hodson Award of the Association is his ongoing legacy.

The story of the Palaeontological Association starts on a Wednesday in the Autumn of 1954. Bill Ramsbottom and I emerged from the, then, Geological Survey Museum into Exhibition Road to bump into Gwyn Thomas coming down from Imperial College, and the three of us caught up with Bill Ball leaving the Natural History Museum. We were all on our way to the South Kensington tube to attend a meeting of the Geological Society of London at Burlington House. It seemed a reasonable economy, important in those days, to share a taxi. During the journey through the slow-moving traffic, talk, as usual, centred on the then current inadequacies of the Geological Society of London. The two papers permitted on a single evening might deal with completely disparate sub-disciplines. Questions were answered only after all of them had been put to the speaker. Of course, there were no ‘seconds’, no cut and thrust, no repartee, all very formal and often so diplomatic that real discussion was hardly forthcoming. The place was always crowded. When two diverse topics were to be aired on the same evening, specialist devotees doubled the attendance and the old parliamentary seating arrangements were very inconvenient. In addition, an archaic election and voting procedure for Fellowship held up the scientific business.

Palaeontologists had been particularly exasperated by the lack of publication facilities in the UK for papers which demanded illustration; in particular Goldring’s Pilton trilobite paper had appeared in Germany, Hudson’s stromatoporoid papers were being published in France, and Parkinson’s statistical investigations of Carboniferous Brachiopoda had been rejected by the Geological Society, ultimately to appear in the American Journal of Paleontology and to be judged as the best paper to appear in that particular year in the prestigious journal.

It was generally felt (probably wrongly) that the bane of the Society was its Dining Club, to which only the elite had access and where the inherited cautious policy of the Society was perpetuated. Certainly suggestions to the ruling hierarchy of the time were abruptly dismissed as impious. For instance, a suggestion that the QJGS [Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society, which later metamorphosed into the Journal of the Geological Society] should be replaced by half a dozen specialists’ journals (of which one should be palaeontological) and of which the subscriptions entitled a Fellow to any two, was rejected without being put to Council as an impractical dream made by innocents with no knowledge of financial matters. When we now see how essentially the same policy has not bankrupted Pergamon, Elsevier and Springer-Verlag, one cannot help regretting that the Society failed to realise that free copy and editorship might be a useful base on which to build a profit-making publishing venture.

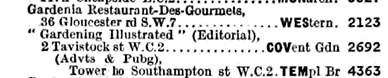

However, the upshot of the taxi-ride was a somewhat derisory resolution to ape our betters and start a Palaeontological Dining Club. Bill Ramsbottom, as a central London resident, was asked to find a place at which we could afford to eat, and call upon a few other palaeontologists to do so. He chose the Gardenia restaurant on Gloucester Road. The proprietor was a polite, foreign gentleman who placed an upper floor at our sole disposal for the evening and generously agreed reasonable corkage for our own wines. Meetings were held after certain meetings of the Geological Society. Frank Hodson acted as recorder and D.J. Carter as wine steward. [The records of these dinners, of which the first was on 15th December 1954, are available in the PalAss archives.]

At the sixth dinner, held on 10th October 1956, it was resolved “to ask Dr R. G. S. Hudson to dine with the Club and to explain his proposals for the Palaeontologists’ Society”. In fact Hudson had no proposals for such a Society, never having heard of such an organisation, but Ramsbottom and the writer knew that he would by the time he ate his dinner. Even so we left it rather late. Having accepted the invitation to eat with the Club he was told by telephone that Bill and I wanted a few words with him. It was thus that the pair of us called at the offices of the Iraq Petroleum Company on the afternoon of 21st November 1956.

We had often discussed the formation of a palaeontological society during our Wednesday meetings when we could spare the time from goniatites which were the raison d’être for our meetings. It was clear that we needed someone of senior status but retaining an element of juvenile irresponsibility. Hudson fitted the specification exactly. The dilemma was that we could not expect a sizeable membership without a quality journal but we could not afford a journal without a sizeable membership. What was needed was an established, apparently sober palaeontologist, who would sign an order for a publication on behalf of a Society, long before the Society had funds to pay for it. Hudson we felt would do this and break the vicious circle. There was however, a particularly difficulty – the embryonic proposals required about ten minutes to explain and no one had ever been able to speak to Hudson for ten minutes without him interrupting and taking over the narrative. On one occasion (at the Annual Meeting of the Palaeontographical Society) I seconded a motion proposed by him, only later in the discussion to find him speaking and finally voting against it. Knowing this idiosyncrasy, Bill Ramsbottom volunteered to get him to be quiet for ten minutes and to keep him to it whilst I briefed him on what he had to say in a few hours’ time.

Bill did a magnificent job, putting his finger to his lips on a number of occasions. Hudson was surprisingly meek. At the conclusion of the diatribe, which had dissected the sins of the Geological Society as seen by the younger palaeontologists and expanded on the subjectively assessed need for a Society and journal devoted solely to exhibiting the virtues of a neglected group of geologists, he merely said “Alright” and launched into a lengthy and rapid exposition of the Middle East Mesozoic stomatoporoids illustrated by prints, enormously enlarged, of cellulose peels of sections which happened currently to be engaging his attention. Characteristic of the times, they were destined to be published in France.

We hurried back to South Kensington to telephone Norman Hughes and Stuart McKerrow at Burlington House where they were attempting to raise the small voice of palaeontology above the scream of grinding axes. They were asked to call at the Geological Survey offices before going on to the Gardenia Restaurant in Gloucester Road. When they eventually arrived at the Survey, they were treated to a repeat performance of that which Hudson had suffered and asked first to nod approvingly at what Hudson would say and secondly, if asked, to accept the job of Vice President and Treasurer respectively and to agree to Hodson being Secretary and Ramsbottom the Editor. All this agreed, we went to eat. As Hudson rose to speak, we were a bit apprehensive. A busy man who could forget his own proposal during the short time it was debated, he might well have forgotten his briefing of a few hours ago. But all was well, everything emerged as it had been presented – indeed, quite a chunk of it was verbatim.

The upshot of the matter was that an Interim Committee was formed, the composition being as follows: Dr R. G. S. Hudson (Chairman), Dr F. Hodson (Secretary), Dr W. S. McKerrow (Treasurer), Dr W. H. C. Ramsbottom (Editor), Mr N. F. Hughes, Dr J. T. Temple and Dr Gwyn Thomas. At a later date, Professor Alwyn Williams was co-opted. A similar account of subsequent proceedings has been printed in Palaeontology, Vol. 1, part 4, 1959. The Interim Committee was instructed to consider in detail the ways and means of founding a Palaeontological Association, to obtain estimates of the cost of publishing a new journal, to submit proposals for a constitution, and to call a meeting in January 1957. Virtually unanimous support was received from leading palaeontologists in Britain.

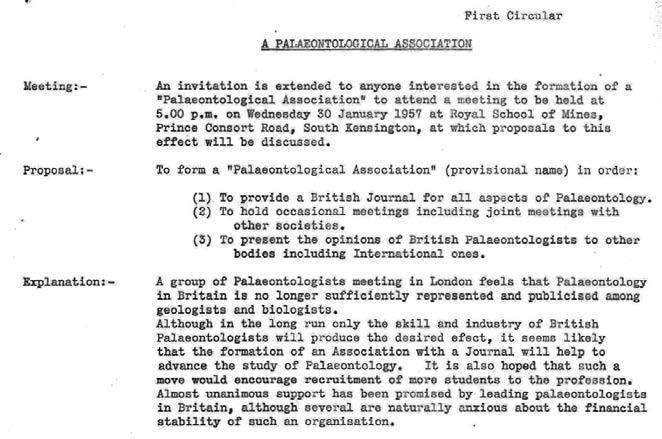

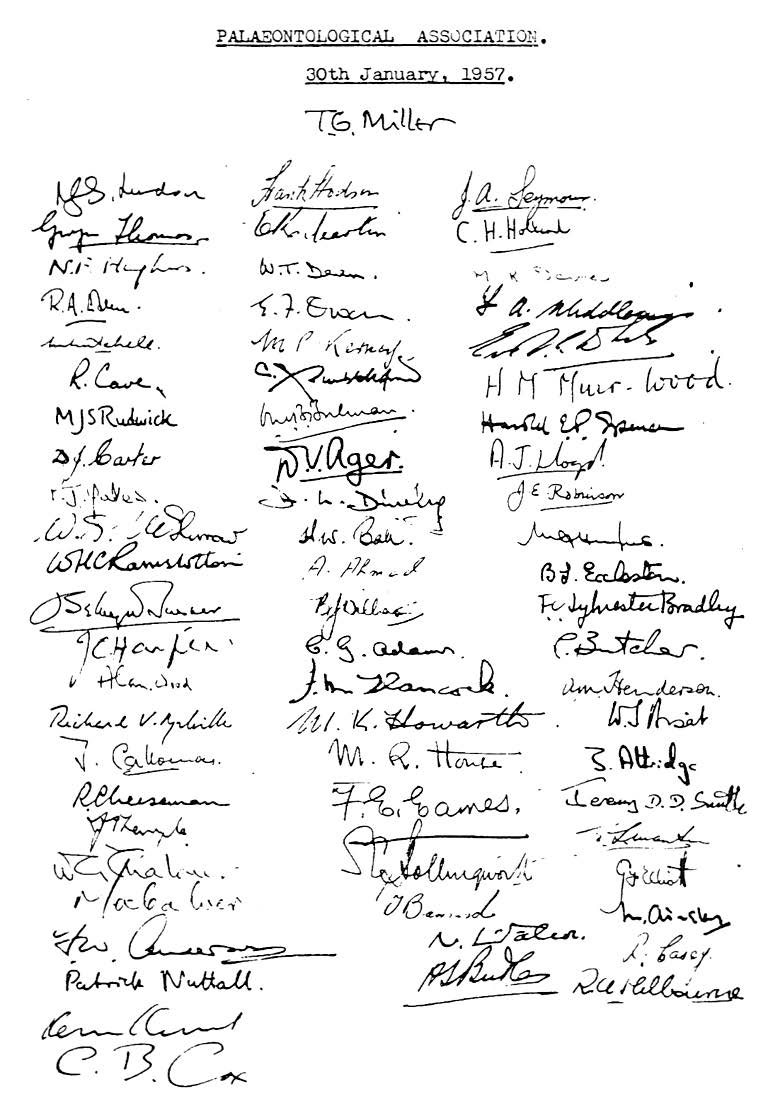

On 1st January 1957 a document known as the First Circular was issued and widely distributed amongst palaeontologists and geologists in Great Britain. It outlined proposals for the formation of an Association, and contained an invitation to a Public Meeting to be held in the Royal School of Mines, Imperial College London, at 5.00pm on 30th January 1957. The response to the Circular was very heartening; slips were returned from over 50% of the 460 copies which had been distributed; over 150 persons signified their firm intention of joining the proposed Association, and about 60 others wished the Association well but were unlikely to subscribe.

Seventy persons attended the Public Meeting on 30th January 1957, where Dr R. G. S. Hudson, who was in the Chair, outlined the need for a Palaeontological Association. Mr N. F. Hughes, acting as spokesman for the Interim Committee, described the events which had led up to the meeting and explained the proposals which were being put forward. It was announced that a second meeting would be held in the near future formally to inaugurate the Association, adopt a Constitution, elect a Council and empower it to collect subscriptions. A full discussion ensued concerning the name and aims of the proposed Association, its relationships with existing societies, the holding of meetings, the proposed subscription, the financial aspects of establishing a new journal offering adequate illustration, and the format of such a journal. A Resolution proposed by Dr E. I. White FRS, and seconded by Dr F. W. Anderson, “that an Association to further the study of Palaeontology be formed” was carried unanimously. A second Resolution, proposed by Mr R. V. Melville and seconded by Professor O. M. B. Bulman FRS and Mr W. S. Bisat FRS, “that Dr F. Hodson, Dr R. G. S. Hudson, Mr N. F. Hughes, Dr W. S. McKerrow, Dr W. H. C. Ramsbottom, Dr J. T. Temple, Dr Gwyn Thomas and Professor Alwyn Williams are elected as an Organising Committee, and are requested to report progress at a meeting to be called in the near future”; also that “this Committee has power to co‑opt” was carried unanimously. The writer continued as Secretary.

The Second Circular, distributed on 13th February 1957, reported the resolutions carried at the Public Meeting, and contained an invitation to the Inaugural Meeting of the proposed new Association to be held at 2.30pm on 27th February 1957 in the Royal School of Mines to adopt a Constitution.

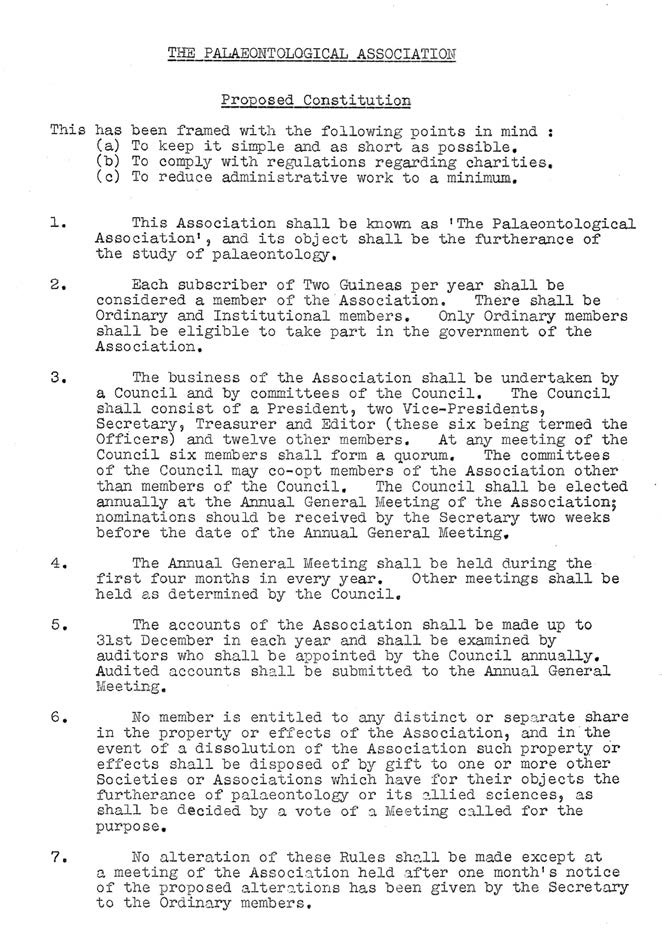

At this Inaugural Meeting, attended by 49 persons, the ‘Proposed Constitution’ was discussed in detail. The following people contributed to the discussion from the floor in the order listed: Messrs Eames, Shirley, Westoll, Thomas, Swinton, Wood, Gill, Ramsbottom, Melville, Eames, Melville, Westoll, Sylvester-Bradley, Barnard, Ainsley, Swinton, Sylvester-Bradley, Curry. With some amendments, it was unanimously accepted. The following were then elected as Officers and Council of ‘The Palaeontological Association’ for 1957. President: Dr R. G. S. Hudson; Vice Presidents: Dr E. I. White, Mr N. F. Hughes; Treasurer: Dr W. S. McKerrow; Editor: Dr W. H. C. Ramsbottom; Secretary: Dr F. Hodson. Fourteen other members of Council: Dr F. W. Anderson, Dr T. Barnard, Professor O. M. B. Bulman, Dr F. E. Eames, Mr G. F. Elliott, Professor T. N. George, Dr Dorothy H. Rayner, Mr P. C. Sylvester-Bradley, Dr J. T. Temple, Dr Gwyn Thomas, Professor T. S. Westoll, Professor W. F. Whittard, Professor Alwyn Williams, and Professor Alan Wood. It was resolved that the Council be authorised to publish a journal containing works of palaeontological interest, and that the Officers of the Association be authorised to act as an Executive Committee of the Council. A Third Circular gave a report of the Inaugural Meeting and called for subscriptions.

The first Council Meeting was held in the Board Room of the Geological Survey Museum at 11.00am on 1st May 1957. Finance, Publications and Meetings Sub-Committees of the Executive Committee (with powers to co-opt) were established to carry out the business of the Association. Appeals for funds to finance the Association, and particularly its proposed new journal, had already been initiated. It was agreed that the name of the Journal should be ‘Palaeontology’, and that two parts a year should be published initially, that it should be Crown Quarto in size, and that it should be printed by the Oxford University Press with collotype plates. Arrangements were made for the first Demonstration Meeting to be held on 29th June at Bedford College, London, and the first Discussion Meeting on Carboniferous palaeontology on 13th–14th December at Sheffield.

At the second Council meeting on 29th June 1957, the writer resigned the duties of Secretary of the Association. Item 2a(ii)of the Council minutes reads: “Dr Hodson expressed his desire to resign from the post of Secretary due to pressure of other work. The council reluctantly accepted his resignation, and recorded its thanks to Dr Hodson for the services which he had rendered, and also its appreciation of his enthusiasm as one of the founders of the Association. Dr Gwyn Thomas was elected to fill the vacancy, as from 29th June 1957. It was decided that Dr Hodson should remain on the Executive Committee”.

The writer felt that the embryonic and infant stages of the Association had been successfully accomplished. The membership had reached 191 (185 individual and six institutional members) and there would be enough money in the bank to pay for Volume 1, part 1 of Palaeontology. There were other things to do. Dr Gwyn Thomas guided the Association through its juvenile stage to maturity so that by the end of 1957 membership was over 300, and by the end of 1958 had reached 412, and this less than two years after the inaugural meeting.

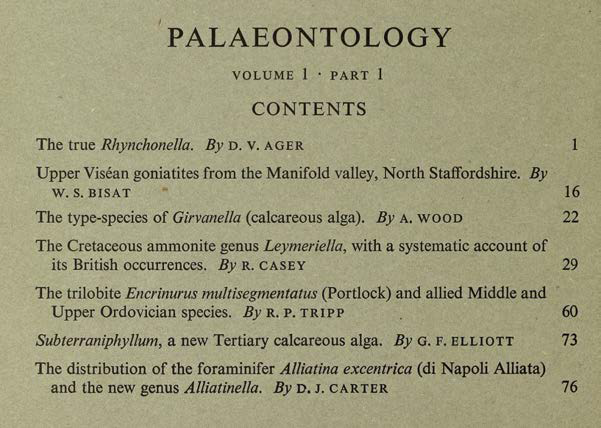

The first Anniversary meeting was held at Sheffield University on 13th and 14th December 1957. Forty-five people sat down to the first Anniversary Dinner ominously held on Friday the 13th, and by that date members had in their possession the first part (published 1st November) of Volume 1 of Palaeontology – probably the finest printed and illustrated scientific publication in the world (subsequently to be exhibited and win an award at the Frankfurt Book Fair). It had cost £568 and its successors in 25 years enriched palaeontological literature with 19,137 pages and 2,661 plates, a ratio of one superb plate to 7.26 pages of OUP print. It is the Association’s biggest asset. How glad we are that we resisted the blandishments of a certain publisher to initiate it for us and let members have it cheaply if institutions could be made to pay through the nose. It was a seductive proposal. Its rejection by the Executive Committee of Council was their wisest decision. R. G. S. Hudson was decisive. Having no certainty of being able to pay, he unhesitatingly signed an order for it. “What happens if we don’t get the cash?” someone asked. “You will have to dig into your pockets”, replied R. G. S. unhesitatingly and with a conviction which showed he believed it. This could not be said about some of his early assurances made to create optimism amongst various people. I used to try to convince myself that he was not really being untruthful, but merely representing a state of affairs as he honestly saw it, a very charitable view; but the Association would not exist but for Hudson’s particular style in getting things moving.

Returning to the Malthusian growth rate in membership in the early years, it was clear that an empty ecological niche had been identified for colonisation. Such growth had eventually to slow down. At the time, it was thought that the carrying capacity (K) of the growth equation might be about 1,000. It is gratifying that 25 years have shown us that this was an underestimate. Perhaps 1,600 is now a better guess, but the initial ‘r’ mode population growth has ended. A punctuated equilibrium type of evolution has been succeeded by phyletic gradualism in which we must seek new needs to be catered for. We must do all we can to leave no unfilled wants. If we do, then another competitor will do what we did 25 years ago.

Frank Hodson (1921–2002)

Emeritus Professor, University of Southampton

Original member of the founding ‘PalAss taxi’

Original Member of the Palaeontological Dining Club

PalAss Council member 1957–1962 (Ordinary Member, Secretary)

Short notes from founding or honorary life members of the Association

What follow are short notes from founding or honorary life members of the Association who were asked recently to contribute any recollections from the early days of the PalAss and comment on any changes they’ve seen over the intervening decades.

Bill Ball:

In the 1950s, palaeontology was undergoing remarkable development, but that development was being seriously retarded by inadequate presentation in discussion and publication. The young bloods of the day frequently met, often over dinner after Geological Society meetings, to discuss how the situation might be improved. At one such dinner Dr Gwyn Thomas and I were delegated to approach several learned societies to see if and how the situation might be remedied. Our first contact was with the Geological Society to see if they would be prepared to increase the format of their Quarterly Journal and enhance the quantity and quality of the illustrations. They declined, but did exactly that some years later. It is ironic that had they agreed at the time of our presentation, the PalAss would possibly never have come into existence!

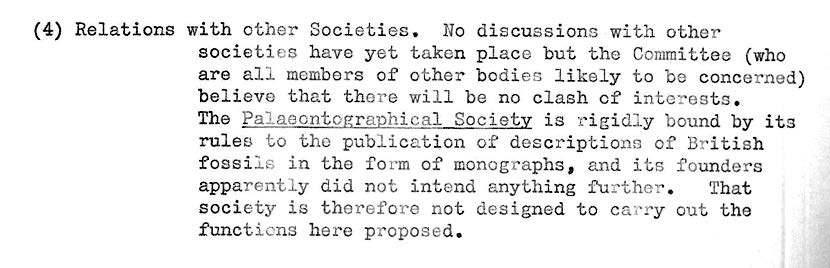

We also had a meeting with the Council of the Palaeontographical Society where we asked if they would consider introducing meetings where palaeontological papers could be presented and discussed and if they would introduce a publication in a smaller format in addition to the large monographs for the publication of shorter papers. This, too, was declined. We may have had meetings with other societies, but here memory fails me.

As a consequence it was evident that the only solution to the problem was the initiation of a new society devoted to the publication of palaeontological papers. It was at this stage that Prof. R. G. S. Hudson became involved and subsequently played a significant role in the inception of the Association. It is also appropriate that the important contribution made by Gwyn Thomas in the design and format of the Association’s publication should be acknowledged.

Harold William (Bill) Ball

Former Keeper of Palaeontology, Natural History Museum, London

Original member of the founding ‘PalAss taxi’

Original Member of the Palaeontological Dining Club

Charles Holland:

In the early 1950s a number of younger palaeontologists working in London and the south of England had become increasingly dissatisfied with the Geological Society’s supposed neglect of their needs, particularly in terms of publication of their work. It should be said that they perhaps lacked knowledge that the Society was not rich and was committed to regular publication of the papers presented to it at its regular meetings. Conversations between Frank Hodson, Gwyn Thomas, Bill Ramsbottom and Bill Ball led to the formation of a Palaeontological Dining Club. In a privately circulated account, Frank Hodson gave details of its meetings which took place at the Gardenia restaurant in South Kensington after meetings of the Geological Society. He gave records of the nine younger palaeontologists who attended the first meeting on 15th December 1954; some 23 members eventually were elected. Meetings continued over several years, and they were pleasant occasions. The restaurant charged only a reasonable corkage. It was at the Club that the idea of a palaeontological association began to develop. As Hodson recorded, eventually he and Bill Ramsbottom arranged to meet Prof R. G. S. Hudson on 21st November 1956 before Hudson came, by invitation, to the Club. The purpose was to discuss the possibility of an Association and publication. Hudson was a very senior and respected palaeontologist and stratigrapher who had moved from his Chair at the University of Leeds to work for the Iraq Petroleum Company and to continue his research while he was there. He was well known to some also for work as an external examiner at the University of London. The Palaeontological Association must see R. G. S. Hudson as a founding figure who was prepared to take the not inconsiderable risk of underwriting the publication of an expensive journal before subscriptions from members of an association were guaranteed to finance it.

Subsequently, amongst other developments, Gwyn Thomas arranged to sound opinion among the British geological community by issuing a circular. The response was good. Two substantial meetings were arranged at the Royal School of Mines. At the second one, which was the inaugural meeting of the Palaeontological Association, a Council was elected, as was an Executive Committee.

The Association was fortunate in the support given later by distinguished presidents who succeeded Hudson: O. M. B. Bulman, Woodwardian Professor at Cambridge, gave authority and dignity in his conduct of meetings; Professor T. Neville George exposed us to a torrent of complex English with that clarity for which Welshmen are so capable of when speaking English. There was wide support of the new Association. I still remember my old chief Professor Leonard Hawkes who, though himself an igneous petrologist, joined the Association for its first five years to give encouragement and support. Once, seated on a front bench in the Geological Society’s meeting room, he was seemingly taking notes of Hudson’s Anniversary Address. “I did not know you were so interested in that subject”, I said to him afterwards. “I was just counting the ers” he said.

But in the early years the Association owed much to the small dedicated group who became the Executive Committee. After Frank Hodson resigned as Secretary to find time to cope with his duties in Southampton, Gwyn Thomas took over from him. He continued to display his ever so capable conduct of business. Stuart McKerrow, a canny Scot at Oxford, provided effective control of our finances. We should certainly remember also Norman Hughes, Fellow of Queen’s College Cambridge, who brought style to our activities. Some will still remember his particular kind of quiet laughter, which he used to combine sympathy with degradation. When a manuscript arrived in shoddy condition, the author expecting a referee to do the work of correction of error or revision to our expected format, Norman would insist that it be sent back before it was assessed scientifically. Speaking of our development as an association, he once said to me “We must not let it get into the hands of the BM” [1].

My own role in all this was a modest one. Gwyn Thomas became more and more concerned with the development of the all-important journal and its plates, so that eventually I came to succeed him as Secretary. One of my early tasks was to assemble material for our first newsletters, the Circulars. I walked with the copy to a small discreet typing agency near Regent’s Park, where two ladies of uncertain age produced a meticulously typed version, which they then posted to the increasing list of members that we provided. I was asked also to arrange the first of a series of so-called Demonstration Meetings at which a few members would show their work and say a little about it. The first of these took place at Bedford College. Afternoon tea was served. It is interesting that after 60 years this has led to the large and impressive winter meetings of recent years. These have become increasingly international in character. Unlike the present British Establishment, the Palaeontological Association will never turn its back on mainland Europe. Palaeontology knows no frontiers.

Charles Hepworth Holland MRIA

Emeritus Professor, Trinity College Dublin

Original Member of the Palaeontological Dining Club

PalAss Council member 1958–1968 and 1974–1976 (Ordinary Member, Assistant Secretary, Secretary, Vice President, President)

Lapworth Medal recipient 2008

Honorary Life Member

Martin Rudwick:

I think I joined the PalAss as soon as it was founded, though I had forgotten – until reminded recently – that I was present at its inaugural meeting. At that time I was teaching palaeontology in the then Department of Geology in Cambridge. Like other twenty-something palaeontologists in Britain I felt the science was rarely getting as much attention as it deserved at Geological Society meetings, or as much space in the then Quarterly Journal. In fact, we felt the Geological Society was moribund; and the Palaeontographical Society was of course limited in impact, despite the fine quality of its monographs. So, the early decision of the PalAss to start a new journal, with the ambitiously – or provocatively – plain title Palaeontology, was hugely welcome. I remember lively discussions with my older Cambridge colleague Norman Hughes, agreeing about the desirability of a generous allowance of high-quality illustrations, in view of the intrinsically visual character of the science; and how this might make economic sense if authors could be persuaded to be less verbose in their prose.

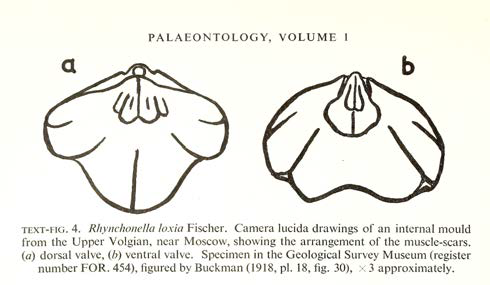

However, the papers in the early volumes of Palaeontology, though often impressive in scientific quality, reflected the character of the science at that time. Palaeontology was above all a handmaid of geology, and the focus of most papers was taxonomic and/or stratigraphical. There was little to suggest that the science might be equally – or more – a branch of biology, and that fossils were the remains of organisms that had once been fully alive and, perhaps, kicking. At the risk of sounding boastful, I believe my own 1961 paper reconstructing the possible feeding mechanism of a certain aberrant Permian brachiopod was the very first in Palaeontology to express in its title an ambition to apply the principles of functional morphology to fossils, though by the end of the 1960s there were plenty. It was also a sign of how the science was implicitly defined at that time, that a referee for my paper – I guessed it was a certain senior British palaeontologist – recommended that it be rejected and submitted instead to a zoological journal. The same referee also criticized my paper for requiring a whole expensive collotype plate to reproduce stills from ciné sequences of my working model of the putative feeding mechanism: not images of any real fossil specimen! However, within the 1960s a truly biological attitude to fossil organisms became commonplace in Palaeontology, well before the appearance in 1975 of the American journal Paleobiology. Although I left palaeontology professionally in 1967, lured away by the equal intellectual challenges of the history and philosophy of science, I have never lost my fascination with palaeontology, and I’m delighted to congratulate the PalAss on reaching its 60th birthday.

Martin J. S. Rudwick FBA

Affiliated Research Scholar, University of Cambridge

Professor Emeritus, University of California, San Diego

Elected Member of the Palaeontological Dining Club

Hugh Owen:

As a member of staff at the British Museum (Natural History) as it then was (now the Natural History Museum, London), I, along with my colleagues, had wind of the possibility of forming an Association to further palaeontology and biostratigraphy in the UK – not before time as we were much the Cinderella of the geological establishment of the day. I recall that the meeting at the Royal School of Mines on 30th January 1957 (after working hours of course) was not only well conducted but elicited real enthusiasm, and thus the Association was born. It amazed me that the eventual membership fees were comparatively low considering the quality of the journal and its contents right from the start, and I think we had to thank the various oil companies for their support in those early days. It was a tribute to the founding committee and the Editor that the first part of our journal was published in November 1957.

I hope that the Association will continue to publish systematic faunal and floral descriptive papers, as well as biostratigraphic, as was intended in those early days – along with the more esoteric computer-generated faunal analyses of modern times. Also, that the refereeing system – a plague in those early days and which led to the formation of the Association – never reverts to ‘establishment’ censorship of new concepts.

Hugh G. Owen

Scientific Associate, Natural History Museum, London

PalAss member for 60 years

Ian Rolfe:

Some of the more unusual memories from my initial time on the Executive Committee of the PalAss were the evening dinners following committee meetings, very far removed from the Geological Society Dining Club’s meetings! These committee meetings took place usually in King’s College, London, where Jake Hancock was a staff member. Jake was a very successful Treasurer of the PalAss for many years, responsible for building up the Association’s large financial reserves. He was also a wine buff – I remember him being astonished at the length and quality of Glasgow’s Ubiquitous Chip restaurant’s wine list. He was also a marvellous bon viveur who introduced the Committee, or those able to make a late evening of it after the Committee meeting, to a delightful small restaurant in Flask Walk, Hampstead, called something like The Poacher’s Bag. It was the venue for some creative PalAss programme planning!

The early form of the Newsletter – the Circulars – were nothing like as professionally produced or as all-encompassing as they are today. I edited them for some years and from 1971 to 1978 produced, with official help, an annual supplement listing palaeontological theses and then-current postgraduate research topics. From this, other members could see what research topics were in the offing or were already spoken for. In those pre-digital days it was difficult to find out who was researching what, and there was always the chance of unwitting duplication of effort.

William D. I. (Ian) Rolfe FRSE

Former Keeper of Geology, National Museums Scotland

PalAss Council member 1965–1976 and 1992–1994 (Ordinary Member, Assistant Secretary, Secretary, Vice President, President)

Honorary Life Member

Tony Hallam:

Socially the early, relatively small, PalAss meetings were pleasant enough, but the general standard of talks rather pedestrian and not involved with topics of much interest or importance to others, such as evolution, extinctions, or palaeobiogeography. Matters have improved considerably over time. One especially gratifying feature in this respect has been the introduction of one-day symposia prior to the main Annual Meeting. Another good thing, also reflected in the Association’s publications, is the increasingly International character of the meetings. In fact, our Association ranks among the best palaeontological societies in the world, the only serious rival being the Paleontological Society based in the United States.

The quality of talks at the PalAss Annual Meetings has improved considerably over time. Many speakers these days are young research students and postdoctoral fellows, who have responded positively to the competition provided by the award of the President’s Prize, which has done much to improve standards of presentation. Also, the introduction of poster sessions has been a valuable innovation.

A further change I have noticed at the Annual Meeting in recent years is the increasing proportion of botanical and vertebrate studies (the micropalaeontologists continue to go their own way). On the other hand, there is a decreasing proportion of invertebrate studies. Practitioners of the study of a number of familiar groups seem to be disappearing, at least in the UK. This is especially true for the group I am most familiar with, the Mollusca, with all-important group the ammonites appearing to be on the brink of going extinct.

Anthony (Tony) Hallam

Emeritus Professor, University of Birmingham

PalAss Council member 1967–1970 and 1982–1984 (Ordinary Member, President)

Lapworth Medal recipient 2007

Honorary Life Member

Robin Cocks:

Stuart McKerrow (Mac) was the only palaeontologist teaching at the University of Oxford when I was an undergraduate there, and he was one of the founders of the PalAss and its first Treasurer. Some years earlier, he and Norman Hughes at the University of Cambridge had got themselves elected to the Geological Society Council, with the keen intention to get that society to publish a separate new journal for palaeontology; however, they failed for a variety of reasons, partly financial (the Society was on its uppers then), but partly because key senior Fellows did not want the prestigious Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society to cater only for the rest of geology and thus lose its panoramic appeal. Comparably, the long-established Palaeontographical Society firmly published only on the systematics of British fossils, without the option of more general arm-waving and discussion in their monographs, and its then officers refused to change.

I went up to Oxford in 1959 as a relatively old ex-National Service soldier, but found that, with the exception of Hugh Torrens, the others reading geology in my big year (yes, all 14 of us), had little interest in fossils, partly because Mac made us learn several hundred Latin fossil names, which seemed too much like the worst homework at school. However, because I already had a substantial fossil collection at home from my childhood years, I persisted with palaeontology and thus Mac persuaded me to join the PalAss in my third year. That year also saw the arrival of an American named Fred Ziegler, who then started his DPhil on the Upper Llandovery rocks and fossils of the Welsh Borderland. Thus Mac persuaded Fred and I to join him at the 1961 Christmas PalAss meeting at Bristol, with us sleeping in Mac’s Dormobile on the driveway of a friend. The core of the meeting can only be described as largely dull: the lectures were half an hour each and the meeting lasted only one and a half days, with the dinner in the intervening evening. There were, I think, around 70 attendees (all British), and I vividly remember that the President, the notable graptolite authority Oliver Bulman (who sat beside the speaker and thus faced the audience), not only fell asleep but snored so loudly that the poor speaker came to an abrupt end. The average quality of the slides was poor: all monochrome (apart from the odd Kodachrome outcrop colour slide) – a far cry from the lurid PowerPoints of today, and very often the glass slides were overcrowded with far too many cramped words illegible near the rear of the room. However, the best thing for me was meeting for the first time half a dozen or so younger people who were at the meeting, some of whom, like Barrie Rickards, I befriended for life.

After graduation the following summer, I went on to do my DPhil on the northern half of the Welsh Borderland and then got a permanent job at the Natural History Museum (nobody thought of postdocs then). Publication then was variably erratic – my first Palaeontology paper was submitted in November 1965 but was not published until September 1967. However, I became progressively more immersed in the PalAss mainly through its Annual Meeting, even leading a one-day field meeting in Shropshire in 1967, and I started the process of becoming an Editor through the personal tuition and kindness of Gwyn Thomas (just up the road at Imperial) in 1968, although I was not formally elected as such until 1969 when I joined Council. The Association’s President then was the formidable Alwyn Williams (later Sir Alwyn), who was highly competent but who did not suffer fools gladly (luckily I largely evaded his eagle eye)! However, the four Editors worked very well together and we much enjoyed the annual lunches given to us at Oxford University Press (OUP), then the publisher of the journal. In those days ‘editing’ included rephrasing other people’s papers (usually on one’s own initiative and without consultation – some authors were surprised when they got their proofs – often, but not always, pleasantly), and we had to mark up all the copy with font sizes etc. after acceptance and before they were sent to OUP. I remained an Editor until 1982.

In the late 1970s I spent three summer field seasons in Newfoundland with Mac, in an area with no motels where we rented the schoolmistresses’ bungalow as they fled south to seek the sun. Thus the evenings were spent writing up, wrapping fossils, smoking, drinking and talking, during which Mac opened up a lot, not only about his naval war experiences (which included a Distinguished Service Cross, or DSC, for gallantry), but about the early PalAss. Apparently, the key smart decision of our founders was to persuade R.G.S. Hudson to be the first President. Hudson was a man with a varied reputation who was often provably unscrupulous and who had made a lot of enemies but who, crucially, following his stint as Exploration Manager of the Iraq Petroleum Company, had the ear of several managers in other oil companies in an age when sponsorship was hard to come by except at the highest corporate level. Thus Hudson (verbally) and Mac (in practice) persuaded various oil companies (led by the Iraq Petroleum Company with a noble £250) to give us a total of £750 on trust before anything was published, with the result that there was almost enough money to pay OUP for the issues of Palaeontology Volume 1 – there were initially only one or two parts published per year. That cracked the ‘chicken and egg’ financial problem, so that, as subscriber numbers gradually increased as the result of the success and attraction of the first two parts, enough cash dribbled in to pay for Volume 2 and so on, which was the start of the policy followed by successive Councils of keeping enough in investments to pay for a year’s printing.

Enormous credit should also go to our first Editor, Bill Ramsbottom of the British Geological Survey, who, working only with experienced OUP staff, alone devised the highly attractive format of the new journal. It was also cunning that Oliver Bulman was invited by the inner gang to be our second President, since he was very much part of the ‘old establishment’, many of whom had been lukewarm about the Association’s foundation. It was during Bulman’s presidency that virtually all the palaeontologists in Britain finally came on board to support the Association (see the Annual reports then printed in Palaeontology at the end of each volume), so that it grew from 372 subscribers in 1957, to 607 in 1958, and 724 in 1959. So, like continental drift (which had been firmly rejected by all my teachers as an undergraduate), the PalAss evolved to become the ‘new’ establishment of today, not just for Britain but for palaeontologists anywhere in the world.

Leonard Robert Morrison (Robin) Cocks OBE

Former Keeper of Palaeontology, Natural History Museum, London

PalAss Council member 1969–1979, 1981–1982 and 1986–1988 (Ordinary Member, Editor, Vice President, President)

Lapworth Medal recipient 2010

Honorary Life Member

John Hudson:

When the Association was founded, I was at the University of Cambridge. I remember Norman Hughes’ enthusiastic promotion, but I thought I was a sedimentologist, a term not then current. In Part II of the Tripos I had read part palaeontology and part petrology, against the advice of both departments; I was encouraged by Jake Hancock who had done the same a few years earlier. For my PhD I was studying the Jurassic Great Estuarine Series, particularly its palaeoenvironment. I quickly came to realise that the fossils would tell me more than the sediments, so I gradually moved over. I published in Palaeontology, and shortly afterwards spent two years at Caltech following a developing interest in the geochemistry of mollusc shells and limestones. There I was joined by Stuart McKerrow on sabbatical from the University of Oxford. I returned to the UK at Oxford, working with Michael House; Stuart remained a close friend and co-worker on the Jurassic. When I was about to move to Leicester, he told me that members of the Editorial board of Palaeontology should all be within 100 miles of London, and “Leicester is 98 miles from London”. A clear hint, and within a few years I became an Editor, including under Stuart’s presidency. Alwyn Williams was President when I first joined Council, in 1968.

In the 1970s the Association was run by a very small number of people. Presidents came and went, but some people on the Executive Committee, which then included the Editors, served for much longer. There were four or five editors each year. Norman Hughes was a dominant force. Gwyn Thomas had a fabulous eye for detail, as did Isles Strachan. Roland Goldring had excellent judgement but illegible handwriting. Jake Hancock, Adrian Lloyd and Ian Rolfe were not Editors but took full part in discussions. Each paper was read by outside referees (strictly anonymous), but also by a Council member who was not a specialist on the group concerned, called an internal reader. Their job was to assess the interest of the contribution to the general palaeontological public; an excellent scheme that I enjoyed participating in.

Much changed on the technical side of producing the journal. I became Press Editor, which involved liaising with the Oxford University Press and delivering manuscripts to them. We ‘press marked’ each paper with instructions for type size and format. At first they still used hot metal type; plates were produced separately and tipped in, but soon they converted to film-set, a great advantage in storage or if re-printing was necessary. Of course all this was long before the computer era. At one of our meetings we were joined by Vivian Ridler, Printer to the University and something of a grandee. He told us he much enjoyed the appearance of the journal but not the dismal grey cover, so we asked the Press to suggest alternatives. They produced a design with an image of a fossil in the centre of the front cover, in various colours. Dark blue prevailed and that is how the cover has appeared ever since. We had just agreed a new contract by gentleman’s agreement when the University decided to close the Printing House; we were sad about that.

Robin Cocks became an Editor shortly after I did. We had discussed the difficulty that students and amateurs experienced in trying to identify British fossils, and proposed a series of publications based on Formations, rather than taxonomic groups as in a monograph. We wrote a joint letter to the Association proposing what we called “Fossils of the x Formation”. This eventually led to the Field Guides to Fossils, of which 14 have been published to date.

John D. Hudson

Emeritus Professor, University of Leicester

PalAss Council member 1968–1977 and 1988–1990 (Ordinary Member, Editor, Vice President, President)

Honorary Life Member

John Cope:

My first experience of the PalAss was the Annual Meeting in Bristol in 1961. I had left Bristol in the second year of a research studentship on my appointment as an Assistant Lecturer in Geology at the then University College of Swansea. Regrettably I could not afford the student subscription of two guineas to PalAss on my research grant of £340 per annum. (To put this into perspective, a week’s field-work in Dorset cost me the princely sum of £5 per week for bed, breakfast, packed lunch and dinner!) My appointment in Swansea on a salary of £800 per annum (some £55 net per month after deductions) was a definite step up. PalAss was the first society I joined, in autumn 1961, and I paid my first annual subscription of three guineas (£3.15).

In those days all research work was specimen-based. The idea that anyone could complete a palaeontological PhD without handling fossils would have been enough to cause apoplexy in many of the members of the Association. At the Annual Meetings (or Discussion Meetings, as they were then known) papers presented were predominantly from established figures and I cannot recall any posters, but there were extensive displays of specimens. Thus in 1961 in Bristol I exhibited a large collection of ammonites from the Upper Kimmeridge Clay of Dorset that I had prepared. The exhibition in that year and many subsequent ones inevitably included problematica with requests for bright ideas of their affinities. In 1961 there were enough displays to fill two large laboratories in the Bristol department and coffee and tea breaks were spent examining these and talking to the exhibitors. There were around 70 members present and then (as now) there was a real informality and great camaraderie amongst those present, which inevitably included some of the ‘grand old men’ of palaeontology; there were few women present. The President (then Professor O.M.B. Bulman) chaired all the sessions.

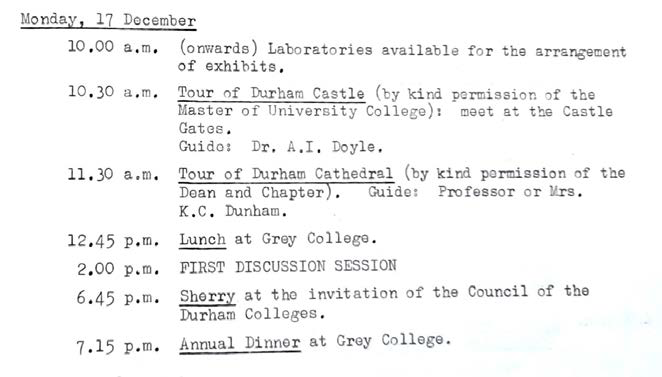

The next year the Annual Meeting was in Durham and that is when I presented my first paper to the Association, on ‘Sexual dimorphism in Kimmeridgian ammonites’. Standard audio-visual aids were 3¼ × 3¼ inches heavy glass slides which had been prepared from glass quarter-plate negatives (3¼ × 4¼ inches); also available was an epidiascope (for projecting directly from maps or books) and a blackboard with a range of chalks. Slides were always projected manually by a technician and talks were punctuated by calls of “next slide please” – shortened to a “next” by some speakers. 35 mm slides appeared in the next couple of years and soon became the standard, although initially 35 mm projectors were manually operated too. In the coffee break after my talk I was quizzed by the President, Professor T. N. George, who concluded his interrogation by shaking my hand. I was then approached by Professor P. C. Sylvester-Bradley (Leicester) who told me that he was preparing a lecture for student societies on ‘Fossil sex’ and he would like to borrow my slides to have copies made. The Durham meeting included a tour of Durham Cathedral conducted by the departmental head, Professor Kingsley Dunham, who then played the organ for us.

In those days the AGM was a separate meeting and always held in London in the spring. Tied in with this was the Annual Address during which a notable figure was invited to talk to the Association. My memories of some of these early AGMs demonstrated that although the speakers may have established names for themselves, some of them had little idea of how to talk about their subject.

In the ensuing years I attended several Annual Meetings and can remember that in 1977 at Reading I exhibited examples of my recently discovered Carmarthenshire Ediacaran fauna. Roland Goldring (Local Secretary) had arranged a glass case for these to protect them from over-eager examination. That meeting – like the great majority of such meetings – was a success, but the self-service Annual Dinner was memorable for the wrong reasons! This was not the last meeting where fossils were exhibited, as I can recall exhibiting Early Ordovician problematica several times in the following years. I have attended all but four of the Annual Meetings since 1977.

I was elected to Council in 1975 and in 1978 became Membership Treasurer, a post now subsumed under the Executive Officer’s job. I soon worked out that the best way of handling the at-times onerous task was to handle the post first thing in the morning every day. Busiest times were in January when the majority of subscriptions were received, late January when some 450 reminders were sent out, and late February when 200 final notices were sent out. I also handled sales of back issues and Special Papers in Palaeontology, non-receipt of parts, address changes, etc. Of course this was well before the days of PCs, so all these tasks were handled manually, ledgers entered up religiously each month and moneys sent off to the Treasurer with a detailed breakdown accounting for every last penny. One of the first changes that I persuaded Council to approve was the introduction of the membership category of Retired Member at a reduced rate. The Membership Treasurer’s job carried with it membership of the Association’s Executive Committee – effectively the Editorial Board for Palaeontology and Special Papers; membership comprised the President, Secretary, Treasurer, Membership Treasurer, Institutional Membership Treasurer and Editors. The ‘Exec’ met in the mornings before Council meetings in the afternoon. After five years as Membership Treasurer I was pensioned off as a Vice-President for two years.

In 1983 I was Local Secretary for the Annual Meeting in Swansea, where I co-organised what was the first pre-conference symposium on ‘Evolutionary case histories from the fossil record’, subsequently published as Special Papers in Palaeontology 33 (eds. Cope and Skelton). This was one of the largest meetings there had been, with 170 members in attendance. Pre-conference symposia have since become the norm. Over the years I have presented papers at many Annual Meetings and was particularly pleased that my talk was accepted for the meeting at University College Dublin in 2012 as it marked the 50th anniversary of my Durham talk. Palaeontology has been the vehicle for some 14 of my palaeontological publications and I hope to publish more there.

I re-joined Council in 2004 as Treasurer, co-opted at first following the death of Jake Hancock, and then formally elected later that year; the job being transformed since the appointment of not only a full-time Executive Officer to the Association, but also of an investment management company to handle the Association’s investment portfolio. After six years in that position I was again elected Vice-President for another two years.

In the duration of my membership PalAss has evolved significantly. Annual Meetings are now much larger, but the main difference in the meetings is that they have become much more international and the AGM is now combined with the Annual Meeting; particularly welcome are the preponderance of younger members and the much higher proportion of female members.

Just as an afterthought, I wondered what has happened to student subscription rates since my days as a research student, and taking UK inflation from then until the present, the equivalent student subscription today would be in excess of £46. This goes to show what a bargain the present student subscription rate is!

The Association today is in rude health, and long may it prosper!

John C. W. Cope

Honorary Research Fellow, Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum Wales

PalAss Council member 1975–1985 and 2004–2012 (Ordinary Member, Membership Treasurer, Treasurer, Vice President)

Honorary Life Member

Euan Clarkson:

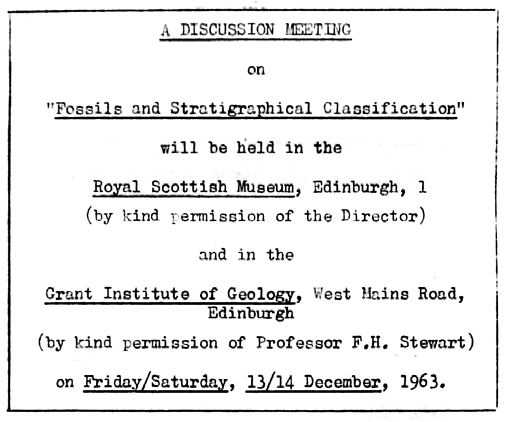

I was still an undergraduate so did not attend the earliest meetings of the Association, but by 1963 I had obtained an Assistant Lectureship in the Geology Department at Edinburgh, and in the December I attended my first PalAss Annual Meeting in that same Scottish city. I have a distant memory that there were fewer than 50 participants, and most of them seemed elderly and very senior, perhaps a little stuffy. In view of their antiquity they seemed somewhat remote and a little scary. But they were not unwelcoming, and this, to a neophyte such as I, was a critical issue. I submitted my first papers to Palaeontology (where else?) in 1965; they were accepted and the advice of the Editors was first-rate and gratefully received. The second Annual Meeting I attended was two years later in Swansea, and it was equally stimulating, but indeed there was a much larger audience than before. In the following years I was unable to attend the Annual Meeting because of family commitments and young children at home. But it was clear that the journal was becoming well-respected, and moreover was attracting very welcome contributions from many parts of the world. Furthermore, the Association launched a cyclostyled Circular, with book reviews, notices of meetings, field-trips etc., and notices of the Association’s medallists.

In 1975, when the Association was 18 years old, the number of delegates to the Annual Meeting far exceeded 100. Sadly, the admirable Department of Geology at Newcastle University, where it was held, was one of the casualties of doctrinaire political meddling in the mid-1980s. There were other such disasters too, but despite the reduction in number of departments which taught our subject, the Palaeontological Association grew and expanded. Indeed, in the following years it went from strength to strength. Numbers of participants grew steadily: in more recent years we have had over 300 delegates to the Annual Meeting. Instead of the nice, but simple cylclostyled Circular, we moved instead to a splendidly produced, printed and coloured Newsletter with notices and reports of meetings, book reviews, photographs, discussion of available mathematical methods, erudite essays, obituaries, notices of PalAss medal recipients, and so much more – a delight for one’s spare time.

Another departure was the publication of our splendidly illustrated Field Guides to Fossils series; excellent and informative, and very good value. Progressive Palaeontology, a meeting for postgraduates organised by postgraduates, was instituted and became highly successful. As the Association grew, it became clear many years ago that an Executive Officer would be needed; this was agreed by Council, and we are really grateful to Tim Palmer and now Jo Hellawell for their hard work. The number of parts per volume of Palaeontology has increased from four to six, and all previous and present issues have been made available online.

Even in the earliest days we had authors and conference delegates from other countries, and, despite being a predominantly British organisation in those days, more and more people from abroad began to come to our Annual Meeting, and to other related meetings. In the 1990s, a forward-looking decision was made to hold the Annual Meeting outside the UK for the first time. There were some protests, of the worried “nobody will go” variety, but most palaeontologists are made of more adventurous stuff, and our first Dublin meeting was well attended, well run, and highly successful. Many other meetings outside the UK have followed, including those in Galway, Copenhagen, Lille, Uppsala, Ghent, Zurich, Dublin (again) and Lyon. The Annual Meetings are always very enjoyable social occasions, as well as being scientifically stimulating.

The Association began, sixty years ago, with a few far-sighted palaeontologists, primarily seeking a new outlet for publication and prepared to work very hard to ensure that the new society and the new journal were successful. Our present vigour, which persists despite our subject being shamefully underfunded, is the result of all this hard work that authors, Editors, Council members and many other fellow palaeontologists have been prepared to put in, to make our Association work optimally. We have come such a long way. Moreover, I believe that, in addition, we have an open, friendly and positive society, welcoming to neophytes and first-timers, not confined to professional palaeontologists alone, and remarkably free of unfriendly in-groups. See to it, my friends and colleagues, that this admirable situation continues.

Euan N. K. Clarkson FRSE

Emeritus Professor, University of Edinburgh

PalAss Council member 1971–1974, 1982–1985, 1998–2000, 2002–2007 (Ordinary Member, Editor, President)

Lapworth Medal recipient 2012

Honorary Life Member

Dianne Edwards:

I can’t believe that it is 20 years since I was PalAss President. Council meetings must have been so boring: I can’t recall anything of interest. We certainly didn’t have the joy of lots of money to dispose of. We were so egalitarian that we did not address issues such as unconscious bias or gender representation. We did start the Progressive Palaeontology (ProgPal) meetings, however, intended to be an informal, cheap, one-day event for postgraduate students. It now seems to have been transformed into a mini Annual Meeting! If I had a minor criticism of the latter it would be that some talks by younger members can be a little premature and would perhaps be more appropriate to ProgPal. The Annual Meeting has certainly grown over the years. Apart from the date being so near to Christmas (being a parent I always thought it was designed to allow my male colleagues to avoid Christmas preparations), I looked forward to it and found that late nights at the bar were always very good for networking. Other domestic problems include being left at a motorway roundabout late at night in deep snow as my colleague was in a hurry to get home – I had no mobile phone in those days of course, but I was able to struggle to a pub about half a mile away. And then there was an Oxford meeting in Wadham College where I spent the night lying on a sofa wrapped in a blanket in front of a gas fire as the cell-with-a-bed part of the ‘suite’ had no heating – and I never did find a bathroom in the vicinity. There have been some great meetings, but I find it a shame that smaller provincial universities seem reluctant to host such conferences.

For me as a botanist/palaeobotanist the Annual Meeting provided the opportunity to be reunited with my geological/palaeontological mentors, mainly members of the Ludlow Research Group and particularly Charles Holland, plus George Sevastopulo in my year in Cambridge and Bev Tarlo from Friends of the Devonian. I won’t risk boring you – except for one major bleat: I deplore parallel sessions. Apart from the social side, I attend the Annual Meeting to find out what is happening outside my own field. Now I feel obliged to attend the palaeobotanical sessions to support my colleagues, and although admittedly these are few, we have to suffer the overdose of a particular topic for which there is often a specialist group meeting elsewhere. I think the talks should be decided by taking the abstracts out of a hat and this translated into the timetable of the programme, rejecting unsuitable ones along the way. Incidentally, talks have improved out of all recognition as have visual aids – except for occasional overcrowded slides, some of which feature lettering requiring Tim Palmer’s binoculars.

Dianne Edwards CBE FRS FLSW FRSE

Distinguished Research Professor, Cardiff University

PalAss Council member 1982–1993 and 1996–1998 (Ordinary Member, Editor, President)

Lapworth Medal recipient 2013

Honorary Life Member

Tim Palmer:

I joined the Palaeontological Association as a new postgrad student under Stuart McKerrow (one of the founder members) at the Department of Geology, Oxford, in 1970, following a Zoology degree. I’ve had close links with the Association throughout my career, first as an Editor of Palaeontology and then on Council as Treasurer. From 1999 to 2016 I was employed by the PalAss as the Executive Officer. This position was established as a part-time work-from-home job, but the Association and the role continued to grow and by the time I retired it was a full-time and demanding position from a dedicated office.

Over the last 20 years, the funding of the Association changed substantially. The growing relationship with our scientific publisher was one of the biggest changes. They took on the production of our journal titles, providing large economies of scale and offering online services that would have been difficult had we remained independent. Income collected through publishing now makes a significant contribution to total annual income and has allowed for a big increase in expenditure on outgoings, such as two salaried posts, and research and travel support for PalAss members.

Another increase in PalAss income has come from donations or bequests from generous people or their families, and these are all commemorated by the titles of our Small Grants and other early-career funds: Sylvester-Bradley, Whittington, Callomon, Stan Wood, Jones-Fenleigh, Hodson.

Of course, the Association’s funds have also accumulated bit by bit, year upon year, through unspectacular policies of thrift pursued by generations of Council members under the beady eye of a series of Treasurers with methodistic inclinations. The overall increase in income has made possible a huge increase in expenditure for the benefit of our members. In fact, in my last year as Treasurer in 1998, the total contribution in grants to members for research, meetings and travel was less than £1,000. Almost 20 years later, total annual expenditure was £100,000, and included funding for new initiatives in outreach and education. This is a highly significant difference in the more recent history of the Association, and the ability to fund these things has really had a positive impact on our science and its public image.

The Association’s own meetings and those of other research bodies are often awarded a generous subsidy from central funds. Our Annual Meeting and the support of other meetings are essential to foster contact and discussion between all of the people in our subject.

Membership of the Palaeontological Association has always been and still is extraordinarily good value. The PalAss supports the palaeontological community all over the world and from the earliest of career stages. I am looking forward to seeing how the Association develops in the future.

Timothy J. Palmer

Honorary Research Associate, Aberystwyth University

Honorary Research Associate, Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum Wales

Former Executive Officer of the Palaeontological Association

PalAss Council member 1980–1988 and 1994–1999 (Ordinary Member, Editor, Treasurer)

Honorary Life Member

Presidents of the Palaeontological Association

| Years | President |

|---|---|

| 1957–1960 | Robert G. S. Hudson |

| 1960–1962 | Oliver M. B. Bulman |

| 1962–1964 | T. Neville George |

| 1964–1966 | Leslie R. Cox |

| 1966–1968 | T. Stanley Westoll |

| 1968–1970 | Alwyn Williams |

| 1970–1972 | W. Stuart McKerrow |

| 1972–1974 | Michael R. House |

| 1974–1976 | Charles H. Holland |

| 1976–1978 | William G. Chaloner |

| 1978–1980 | Harry B. Whittington |

| 1980–1982 | William H. C. Ramsbottom |

| 1982–1984 | Anthony Hallam |

| 1984–1986 | Charles Downie |

| 1986–1988 | L. R. M. (Robin) Cocks |

| 1988–1990 | John D. Hudson |

| 1990–1992 | John W. Murray |

| 1992–1994 | W. D. Ian Rolfe |

| 1994–1996 | Richard A. Fortey |

| 1996–1998 | Dianne Edwards |

| 1998–2000 | Euan N. K. Clarkson |

| 2000–2002 | Christopher R. C. Paul |

| 2002–2004 | Derek E. G. Briggs |

| 2004–2006 | Peter R. Crane |

| 2006–2008 | Michael G. Bassett |

| 2008–2010 | Richard J. Aldridge |

| 2010–2012 | Jane E. Francis |

| 2012–2014 | Michael J. Benton |

| 2014–2016 | David A. T. Harper |

| 2016– | M. Paul Smith |

Annual Meetings

| # | Year | Location |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | 1957 | Sheffield |

| 2. | 1958 | Cambridge |

| 3. | 1959 | Birmingham |

| 4. | 1960 | Glasgow |

| 5. | 1961 | Bristol |

| 6. | 1962 | Durham |

| 7. | 1963 | Edinburgh |

| 8. | 1964 | Manchester |

| 9. | 1965 | Swansea |

| 10. | 1966 | Imperial College |

| 11. | 1967 | Exeter |

| 12. | 1968 | Southampton |

| 13. | 1969 | Birmingham |

| 14. | 1970 | Belfast |

| 15. | 1971 | Cambridge |

| 16. | 1972 | Oxford |

| 17. | 1973 | Hull |

| 18. | 1974 | Bristol |

| 19. | 1975 | Newcastle |

| 20. | 1976 | Liverpool |

| 21. | 1977 | Reading |

| 22. | 1978 | Keele |

| 23. | 1979 | Cardiff |

| 24. | 1980 | Edinburgh |

| 25. | 1981 | Exeter |

| 26. | 1982 | Sheffield |

| 27. | 1983 | Swansea |

| 28. | 1984 | Cambridge |

| 29. | 1985 | Aberystwyth |

| 30. | 1986 | Leicester |

| 31. | 1987 | Bristol |

| 32. | 1988 | Aston |

| 33. | 1989 | Liverpool |

| 34. | 1990 | Durham |

| 35. | 1991 | Dublin |

| 36. | 1992 | Southampton |

| 37. | 1993 | Leeds |

| 38. | 1994 | Glasgow |

| 39. | 1995 | Galway |

| 40. | 1996 | Birmingham |

| 41. | 1997 | Cardiff |

| 42. | 1998 | Portsmouth |

| 43. | 1999 | Manchester |

| 44. | 2000 | Edinburgh |

| 45. | 2001 | Copenhagen |

| 46. | 2002 | Cambridge |

| 47. | 2003 | Leicester |

| 48. | 2004 | Lille |

| 49. | 2005 | Oxford |

| 50. | 2006 | Sheffield |

| 51. | 2007 | Uppsala |

| 52. | 2008 | Glasgow/Hunterian |

| 53. | 2009 | Birmingham |

| 54. | 2010 | Ghent |

| 55. | 2011 | Plymouth |

| 56. | 2012 | Dublin |

| 57. | 2013 | Zurich |

| 58. | 2014 | Leeds |

| 59. | 2015 | Cardiff |

| 60. | 2016 | Lyon |

| 61. | 2017 | Imperial College |

Annual Addresses

| Year | Presenter | Title |

|---|---|---|

| 1958 | O. M. B. Bulman | The sequence of graptolite faunas |

| 1959 | G. Regnell | The Lower Palaeozoic echinoderm faunas of the British Isles and Balto-Scandia |

| 1960 | R. G. S. Hudson | Tethyan faunas |

| 1961 | T. M. Harris | Fossil cycads |

| 1962 | E. I. White | A review of the habitat of the first chordates |

| 1963 | L. R. Cox | Molluscan relationships and recent finds |

| 1964 | T. N. George | Morphogeny in the spirifers |

| 1965 | T. S. Westoll | Problems of the arthrodiran fishes |

| 1966 | M. Florkin | Palaeobiochemistry |

| 1967 | A. Williams | Evolution of shell structure in articulate brachiopods |

| 1968 | M. Black | Taxonomic problems in the study of coccoliths |

| 1969 | P. L. Robinson | Problems in the study of Triassic vertebrates |

| 1970 | W. H. Blow | Biostratigraphy and phylogenetic concepts in the Cenozoic Globigerinacea |

| 1971 | D. Nichols | The water vascular system in living and fossil echinoderms |

| 1972 | C. Downie | The Palaeozoic acritarchs |

| 1973 | P. C. Sylvester-Bradley | Oysters and Jurassic shorelines |

| 1974 | M. Lindström | The conodont apparatus as a food-gathering mechanism |

| 1975 | W. G. Chaloner | The palaeoclimatic significance of fossil plants |

| 1976 | R. J. G. Savage | Evolution in carnivorous mammals |

| 1977 | M. J. S. Rudwick | Charles Lyell’s dream of a statistical palaeontology |

| 1978 | E. N. K. Clarkson | The visual system of trilobites |

| 1979 | J. H. Callomon | Jurassic ammonites in time and space |

| 1980 | G. R. Coope | Terrestrial ecosystems of the Upper Pleistocene |

| 1981 | P. M. Kier | Rapid evolution in echinoids |

| 1982 | S. J. Gould & C. Patterson | Palaeontology, evolution and systematics |

| 1983 | A. Seilacher | Evolutionary pathways in primary and secondary soft bottom dwellers |

| 1984 | Y. Coppens | Hominid evolution |

| 1985 | B. Runnegar | Molecular palaeontology |

| 1986 | D. M. Raup | Extinction |

| 1987 | A. J. Charig | Ornithischian dinosaurs evaluate cladistic method |

| 1988 | J. Franzen | The Eocene lake of Messel and its early horses |

| 1989 | D. Edwards | Pioneering plants |

| 1990 | P. Westbroek | Emiliania huxleyi as a model organism for evaluating the sciences of life and earth |

| 1991 | D. E. G. Briggs & S. Conway Morris | The Burgess Shale: new vistas on the history of life |

| 1992 | A. H. Knoll | The basis of inference about Precambrian evolution |

| 1993 | A. B. Smith | Molecular and palaeontological perspectives on echinoderm evolution |

| 1994 | B. Sellwood | Mesozoic palaeoclimate: evaluating General Circulation Model predictions against geological evidence |

| 1995 | P. Janvier | The dawn of vertebrates. Character versus common ascent in the rise of current vertebrate phylogenies |

| 1996 | R. McNeill Alexander | All-time giants |

| 1997 | J. R. Cann | Hydrothermal vent communities from the origin of life to the present day |

| 1998 | C. E. Brett | Evolutionary ecology of mid-Palaeozoic marine faunas |

| 1999 | P. R. Crane | Palaeontological evidence for the early evolution of flowers |

| 2000 | D. Walossek | Exceptional preservation of Cambrian ‘Orsten’ type fossils |

| 2001 | R. A. Fortey | Deducing life habits of trilobites: science or scenario? |

| 2002 | H. Torrens | The life and work of S.S. Buckman (1860–1929) geobiochronologist and the problems of assessing the work of past palaeontologists |

| 2003 | M. J. Benton | Palaeontology and the future of life on Earth |

| 2004 | S. Bengston | Palaeontologia de profundis |

| 2005 | J. Kennedy | William Buckland and the rise of palaeoecology |

| 2006 | A. Boucot | What should go into a systematic description |

| 2007 | A. Lister | Evolution in an Ice Age |

| 2008 | J. A. Clack | The emergence of tetrapods: how far have we come in the last twenty years and where can we go in the next? |

| 2009 | L. Witmer | Digital dinosaurs |

| 2010 | A. Gale | Ancient origin of the deep sea fauna: evidence from the fossil record |

| 2011 | P. N. Pearson | Climate and evolution in Cenozoic oceans |

| 2012 | C. Stringer | New views on the origins of our species |

| 2013 | M. Coates | Sharks and the deep origin of modern jawed vertebrates |

| 2014 | A. M. Haywood | Understanding ancient Earth climates and environments using models and data |

| 2015 | J. R. Hutchinson | Computer modelling and simulation of extinct organisms: its utility and limitations for reconstructing the evolution of locomotor behaviour |

| 2016 | M. Gouy | Molecular thermometers: ancestral sequence reconstruction uncovers the history of adaptation to environmental temperature along the tree of life |

| 2017 | M. A. Purnell | 101 uses for a dead fish. Experimental decay, exceptional preservation, and fossils of soft bodied organisms |

Footnotes

[1] B.M. was our common expression for the then ‘British Museum (Natural History)’.